When I buy a saxophone, I'm very quick to decide to replace all the pads. I often buy a sax and it plays okay. Sometimes, it plays well. So I take it completely apart and, as part of my tune-up, I replace all of the pads. Many of the pads could be reused, but I replace them all. Why? Two reasons.

First, I don't buy horns to resell per se. I buy a sax, generally a reputable vintage sax, to see if when rebuilt I will like it better than my favorite sax. If it doesn't make the mark, I donate it or resell it. Obviously, by donating a sax I don't make a profit. It turns out that the same is often true with reselling a saxophone. If I bought an old saxophone, cleaned and adjusted it, and resold it, I might make a profit, but that's not my hobby. My hobby is to get it playing as best as possible. That can't be done on old mismatched pads, in my experience.

The often seen statement describing a saxophone that is for sale is "playing well on older pads." Or the seller says "some pads may need replacing in the near future." I guess replacing a few pads to keep the horn playing is fine for a grade school student whose parents don't think that the saxophone will interest the student for long. Or for somebody on a really tight budget (although new pads are cheap if you do you own sax work). But for all other situations, trying to guess which pads should be replaced is simply not worth it. From the used horns that I have seen, it is only when the pad is really, really bad (and really, really obvious) that it gets replaced. That is like waiting for the core to show on your tires to decide that they need replacing.

I think I can get to Las Vegas on this one. I don't see any light coming through.

And the same players that won't spring for new pads generally have a drawer full of mouthpieces. Really? A $250 Otto Link sitting in the drawer and they are willing to go cheap on pads?

Because I have the saxophone already taken apart when I look at the pads, I simply replace them. Even if they look good. First, I'm trying to determine whether I like the horn when compared to my other horns. I can't do an apple to apple comparison if one horn has old mismatched pads on it. Second, I've found that "good looking" older pads can be junk. Even popular brand name pads can go bad and still look good.

I just finished completely rebuilding a 1951 Conn 10M. It had eleven different styles and vintages of pads on the horn. Clearly, it had gone through the "this pad looks okay" type of care for many years. I could also tell that some of the pads had been replaced without the keys having been removed (and lubricated, swedged, etc.). It had received the type of maintenance where the owner tells the repair person "Do the cheapest stuff to get the horn to play." Or the flip side, where the repair person thinks "Replacing two or three of the worst pads will be such an improvement that the player will be thrilled." After a couple of decades of this type of "service," the horn gets put in the closet, or sold, or given away.

One reason is that the "perfectly good older pads" are leaking. Not leaking so that a leak light shows, which is why they are considered "perfectly good." The problem with older perfectly good pads is that they have deteriorated in a way that makes the leather very porous. I think that it could be years of high moisture that causes the deterioration. Sometimes the pads look stained, but other times not. It is hard to tell which ones are suffering from "rotten leather." So, I just replace them without having to guess about each pad's condition or quality.

Below is an example of a "perfectly good pad" that is extremely porous. This horn had several different types of pads on it and they varied from obviously old and crappy to brand new (although I suspect that the "new" pads were new many years ago when the horn was put away in the closet). So by new, I mean this pad had the least amount of hours of play on it.

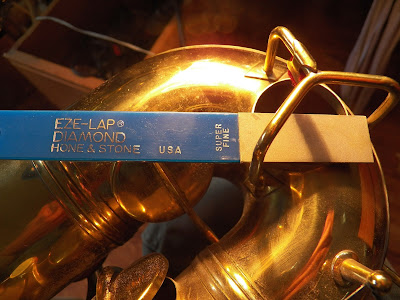

I'm going to scratch the pad with my fingernail. I don't have particularly sharp fingernails and I'm just doing this to show you how easily the leather tears. The leather looks really good, in fact, it hardly even has a seat ring set in the leather. It would not be a pad that would be replaced in a "this pad looks okay" type of maintenance program.

This would not happen with a new pad. New leather is very tough, especially the kangaroo leather pads.

Well, don't do that to an old pad and just reuse it, right? No. Here is how I came to find out that some leather pads were "rotten." I was cutting up old pad leather to use on various parts of the saxophone when I did a rebuild, usually on the "U" posts that stabilize a long key rod. Lining the "U" with leather holds the rod more securely while still allowing it to rotate and not make any noise. I found that when scavenging old pads that had just been removed during the rebuild, some had tough leather and some had a weird "fluffy" leather. When applying contact cement glue to the "fluffy" leather, it simply passed through the leather, making it grip the key rod in the "U". The easily torn leather was permeable to the glue. It was also permeable to air.

I could hold the easily torn leather to my lips and blow through it. I was amazed at how easy it was to blow through the leather. Not very scientific, but it seemed to me that pad leather that "passes gas" is not what I wanted. That old leather would keep light from shining through, but it was like having pads made out of denim. Several pads with "rotten" leather would keep a horn from passing the vacuum test when checking a horn for leaks.

(In fact, when you do a vacuum test, if the pads and neck tenon are properly sealed, the slow loss of vacuum can only be from air passing through the leather and felt, past the tone hole rim, and back out through the leather and into the body of the sax. The less pourous the leather, the less loss of vacuum. Some synthetic pads would eliminate this, however, to date they all seem to have their own issues and they haven't become popular.)

One of the pads on my project sax (the B bell pad) seemed to be identical to the pad that was easily torn. The leather on that pad was much better, probably because it hadn't been exposed to moisture as much. Still, the leather was quite permeable and, since I have no idea the quality of the old pad, it gets replaced.

I haven't found a good non-destructive test to determine whether the leather on an old pad is still good. Not looking good. That's easy. But functioning good. It is possible to scrape the pad inside of the seat ring and, assuming that the leather is strong, then reuse it (although it might have a scuff). But that might also pull the seat ring out of round and it wouldn't sit back in the same place. Again, for the cost of new pads, new high quality pads, I just replace them all.

I did take some video of the "fingernail" test on some other pads. I couldn't get a kangaroo pad to tear by using my fingernail. I couldn't even get it to tear using a dental pick. Nor could I blow air through the leather. Here is a Roo pad that I stained for a different project and then never used. There is a big difference in leather strength and permeability. The pad is also firmer and requires more care in floating, but worth it in my opinion.

Here is a look at a Conn Res-o-pads. Probably original to the 1951 10M. This was a bell pad on another project and had "survived" for decades because it hadn't been exposed to as much moisture.